A genetic tool could play an important role in protecting the caribou, a wildlife species

and national symbol, whose population is in decline.

In Québec, the status of caribou populations is a concern and the focus of conservation efforts. To preserve the species through better monitoring, researchers and biologists from Université Laval and Québec’s ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs (MFFP) have pooled their expertise to develop a DNA chip for the caribou.

The latest and most significant demographic decline has been noted among the migratory caribou, found mostly in northern Québec. The George River herd went from 823,000 in 1993 to 8,900 in 2016. Leaf River saw its caribou population decline by approximately 600,000 to 181,000 between 2001 and 2016. There are three types of caribou (called ecotypes) in Québec: barren-ground, woodland and mountain. While they differ in their behaviour and ecology, they cannot be distinguished by looking at their physical features.

What is a DNA chip?

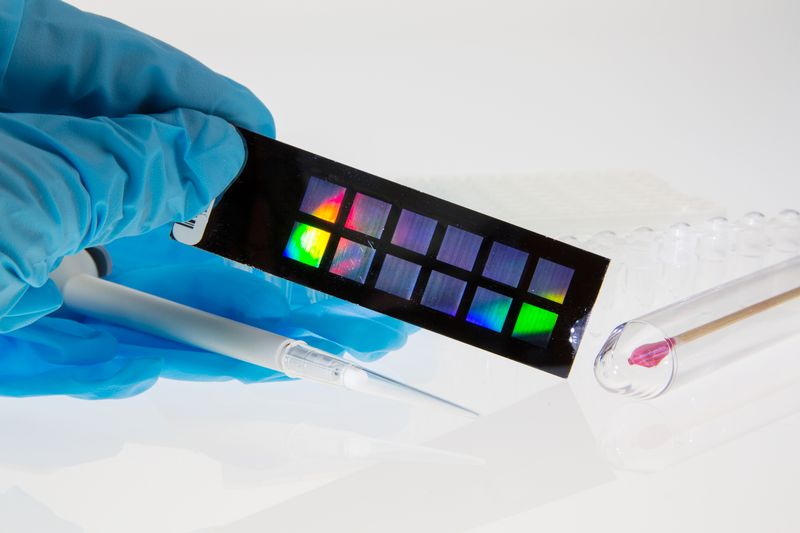

A DNA chip – also known as a biochip – looks like a microscope slide (glass, silicon or plastic). It holds pieces of DNA from a species. When you place a DNA sample into the chip, it can determine if the sample contains DNA from the species in question. In this case, the DNA chip will be able to identify the three caribou ecotypes, making it easier for wildlife conservation officers to do their job.

Example of DNA chip

“What’s novel about our project is that there was no caribou biochip before. In fact, there are very few biochips for wildlife, even though the technology has been used for a while in humans, mice and farm animals,” explains Claude Robert, a researcher at the Department of Animal Science at Université Laval.

To ensure the biochip’s efficiency, researchers are trying to identify unique DNA regions for each of the three caribou ecotypes. This process is underway and should be completed in April 2019. “We’ll probably end up finding millions of differences among each of the caribou groups. The challenge is to choose the genetic signature unique to each one,” adds Claude Robert.

The team is also working on a Web portal, which will facilitate the interpretation of results obtained with the biochip. “Biologists will be able to download the data generated with the tool and then send them to our Website, which will then make the genetic analysis,” says Claude Robert. It will be possible to know the origin and genetic variety of each sample. This information will provide an accurate picture of the status of the caribou. One thousand samples, collected by the MFFP since the early 2000s and already catalogued, will be used to develop the biochip.

“We’ll be able to just take a fragment of flesh, hair or skin from the animal and use the biochip to identify its ecotype. The tool will be tremendously useful in many areas of our work involving the protection, management and conservation of various groups of caribou in Québec,” says Joëlle Taillon, biologist and researcher in charge of studying the three types of caribou ecotypes for the MFFP.

The technology will join the range of tools already used to monitor caribou populations.

DNA chip serving justice

The caribou DNA chip is expected on the market in April 2020. MFFP researchers already see the potential for this tool, which will be used to identify caribou, but also support wildlife conservation officers during their investigations. For instance, the information provided by the biochip could be used as evidence in court in poaching cases. The woodland and mountain caribou have a special legal protection in Québec, making it all the more important to identify the individual’s ecotype.

“When they get to a butchering site, wildlife conservation officers sometimes come across an entire carcass, but often they find only part of a carcass or traces of hair or blood. In this situation, they must be able to accurately determine the caribou ecotype involved, since the rules and regulations vary depending on each group,” explains Vicky Albert, biologist and head of the forensic lab at the MFFP.

Given that caribou can also be found in different Arctic regions of Europe and Russia, researcher Claude Robert would like foreign biologists to also have the chance to use the DNA chip to protect caribou on their territory.